Postpartum Care: These new and growing services offer much-needed mental health support in the fourth trimester.

To Meghan Doyle, co-founder and CEO of Illinois-based hybrid perinatal clinic Partum Health, the experience of entering motherhood felt like “falling off a cliff.” It’s an apt metaphor for the drop-off in maternal health care after giving birth in the United States. As a pregnant person, you’d typically have anywhere from 10 to 15 visits with your doctor at key checkpoints of pregnancy—but the harness unclips at childbirth, leaving you untethered from the medical system as you enter the uncharted territory of new parenthood. It’s in this space that a new slate of platforms, services, and communities are springing up, aiming to support the mental and emotional health of birthing people while they learn the ropes of postpartum life.

The Current Standard of Care for Postpartum Care

The current standard of postpartum care in this country includes just one checkup at the six-week mark after giving birth, which nearly every survey, statistic, and study on the topic suggests is insufficient. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released research in 2022 finding that maternal mortality is most common in the year after a baby is born, with mental illness (including overdose and suicide) as a leading cause. Rates of postpartum depression in America spiked during the pandemic1 and have been on the rise for much longer. In fact, perinatal mood and anxiety disorders (PMADs)—an umbrella term for pregnancy-related mental illness—now affect as many as one in five U.S. moms and double that number of Black mothers due to the social determinants of health, or the environmental factors where such mothers disproportionately live that put them at a health disadvantage (such as lack of access to education or housing). It’s hardly surprising in this context that new moms regularly report feeling unprepared and unsupported postpartum care.

The Postpartum Care Gap

This glaring postpartum care gap isn’t new or isolated in nature; it reflects “the historical de-prioritization, in both research and funding, of women’s health more generally,” says Melissa Dennis, MD, an OB/GYN and chief medical officer at Partum Health. In recent years, awareness of the problem has grown: The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), in 2018, and the World Health Organization (WHO), in 2022, each called for expanding and deepening postpartum care. And in 2024, new third-party providers will finally do just that, supporting birthing people from the moments just after childbirth through the fourth trimester.

The emergence of this support comes in tandem with a new understanding that the postpartum period is not just a transition for the newborn coming into life. It’s also both a recovery period and socioemotional transition for the birthing person, the latter of which is at the heart of matrescence, a term coined by anthropologist Dana Raphael in the 1970s to encapsulate the becoming-a-mom version of adolescence (and the complex identity change that this transition entails).

Maternal Care Offerings

With these medical and ideological realities of the childbirth experience in mind, Partum Health offers maternal care continuously throughout the prenatal and postnatal periods. A team-based model brings together perinatal services like acupuncture, physical therapy, lactation support, and doula care in one place, both in person and online. The company raised $3.1 million in September to expand from Illinois to Texas in 2024, as well as grow its insurance coverage (it’s currently in-network with four providers for clinical care) and create digital-centric versions of its offerings so that it can move into additional markets more quickly.

The idea sprang from Doyle’s own experience panic-Googling things like, “how to tell if you’re bleeding too much postpartum” and texting friends for breastfeeding tips. So much of her strain and stress was caused by a disconnect between her needs and the default mode of care: “It was like, ‘Call us if you need us,’” Doyle says, referring to her doctor’s office, “rather than, ‘We recognize you just underwent a massive physical health event, and you need help, and here it is.’”

Add on the pressing need to care for a brand-new human being while recovering, and it’s easy to see why a birthing parent might feel overwhelmed and under-equipped. “You’re sleep-deprived, and you do not feel like you know what you’re doing, and perhaps you’re breastfeeding, which can be depleting, and maybe you also need to prepare food,” says Monique Rainford, MD, an OB/GYN and the author of Pregnant While Black. “If you’re a person of color, there’s also a higher chance that you’re dealing with a financial or housing stressor…and on top of all that, you have to enter a health-care environment where there may not be culturally sensitive care or where the clinicians have implicit bias against you.”

The Importance of Postpartum Support

In a June Babycenter survey of nearly 2,000 U.S. moms with a child under the age of 6 months, just 41 percent said they received all the support they needed upon leaving the hospital. The numbers are even worse when broken down by race: Just 22 percent of Asian American Pacific Islander (AAPI) mothers, 32 percent of Black mothers, and 38 percent of Hispanic mothers reported having the postpartum support they needed in comparison to 44 percent of white mothers.

Boram Nam, co-founder and CEO of Boram postnatal retreat in New York City, and one of Well+Good’s 2023 Changemakers, was once one of those ill-supported new moms. “I was so exhausted physically, but I couldn’t take leave because my startup at the time was getting acquired, so I also had no time to assess my emotions—that I felt guilty, sad, and isolated,” she says. Her friends back home in South Korea, however, had a very different birth experience. It’s customary for South Koreans to stay in postpartum centers2 called sanhujoriwon for 14 days after childbirth, where they’re offered recovery care and breastfeeding support. (Elsewhere in the world, cultural norms similarly recognize the necessity of social support postpartum3. In Latin America and China, there are postpartum periods during which others handle chores and help mom rest, recuperate, and bond with baby. And across Europe, it’s common for midwives to visit new moms at home after childbirth to provide similar care and lactation help.)

The Boram retreat in New York, which opened in 2022, is a version of the South Korea sanhujoriwon optimized for U.S. life, with stays offered for three, five, or seven nights (from $3150) designed to “serve as a segue between hospital and home,” says Nam. Guests are assigned a private luxury room (equipped with a bassinet for baby) where they can stay with a support person and receive round-the-clock care and lactation support; they also have access to a 24/7 staffed nursery and group workshops on things like swaddling and infant CPR.

To expand Boram’s reach and accessibility, Nam also launched the digital platform Boram Anywhere in July, which offers virtual support and access to text messaging with lactation consultants and perinatal mental health specialists (from $100 a month). Boram is also raising a $3 million seed round to staff up Boram Anywhere and integrate it as an employee benefit with various companies, as well as open a second location of its postnatal retreat in 2024.

Postnatal Retreats in the US

In other parts of the country, similar luxury postnatal retreats are also popping up, including The Village Postnatal Retreat Center, which opened in San Francisco in July; Fourth Trimester Postnatal Retreat, which launched in Washington, D.C., in September; and Ahma & Co, which recently launched a waitlist for its soon-to-come retreat in Los Angeles.

In such facilities, postnatal care starts right when a new parent leaves the hospital—which is when it’s deeply needed, given that nearly one in five maternal deaths occur in the first week postpartum. That’s also why New York City maternity care clinic Oula, which launched in 2021 and is opening a third clinic in 2024, arranges a nurse checkup by phone in the first week postpartum, rather than at six weeks out—by which point complications (including anxiety and depression symptoms) can be well underway, says co-founder and COO Elaine Purcell.

Paradoxically, as many as 40 percent of new moms don’t even attend that traditional six-week appointment, often citing the very kinds of mental challenges4 that could be alleviated with care. To better reach people with support right when and how they need it, Oula also offers virtual drop-in postpartum office hours (hosted by a doula or lactation consultant). And in 2024, the company will bring on Jessica Vernon, MD, an OB/GYN who’s outspoken about her experience with postpartum depression, to offer formalized mental health support (via group therapy and medication management) in response to rising rates of PMADs.

The Dire State of Maternal Mental Health

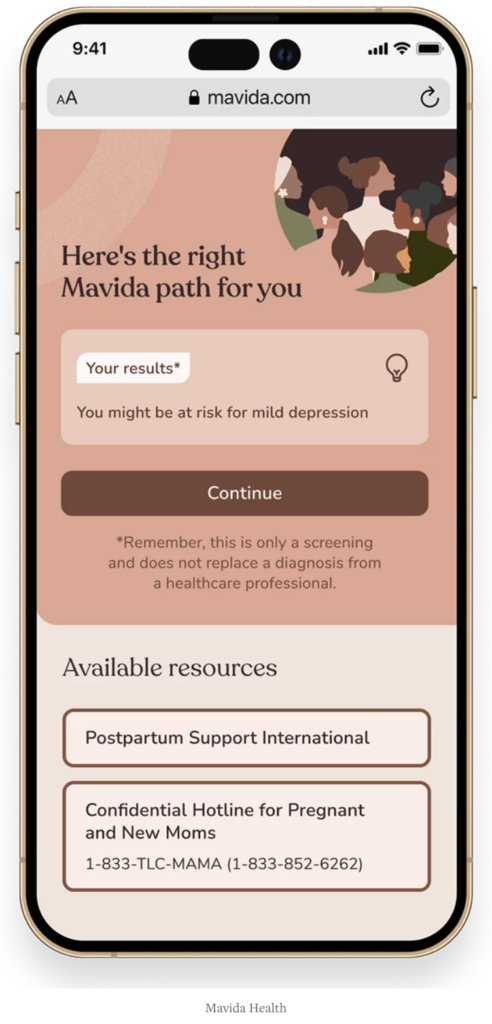

New brands are also addressing the specific factors underlying the dire state of maternal mental health5. “The female reproductive hormones increase to levels that they never have before during pregnancy, and then they plummet postpartum, creating the most extreme difference of hormones that we ever see,” says reproductive psychiatrist Sarah Oreck, MD, co-founder and CEO of virtual maternal mental-health platform Mavida Health, which launched in California in September. That significant hormonal change can lay the neurological groundwork for depression, anxiety, and other mood disorders6. It’s no wonder that 85 percent of birthing people get the “baby blues,” or feel sadness and mood swings in the first few weeks postpartum, even if they don’t meet the qualification for a PMAD.

The ubiquity of the baby blues can make it tough for a new parent to know if what they’re experiencing is problematic, says Dr. Rainford. “As obstetricians, traditionally we weren’t trained on mental health, so to ask women to figure out if they have an issue themselves feels ridiculous,” she says. That’s where Mavida Health comes into play. The platform’s onboarding quiz employs the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Screener (EPDS) to assess whether a new mom may benefit from clinical care; a respondent chooses how much they agree or disagree with statements like, “I have been able to laugh and see the funny side of things,” and “I have blamed myself unnecessarily when things went wrong.” After raising $1.5 million in pre-seed funding this year, Mavida Health—which currently offers individual and group therapy along with medication management—plans to expand its offerings to New York and begin to accept insurance (the $99 annual membership fee and care fees are out-of-pocket for now) in 2024.

Help for Postpartum Depression

Another notable development: In August, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first pill to treat postpartum depression, called Zurvuvae, which is slated to launch by year’s end. (Previously, there was only the IV medication Zulresso, which was approved in 2019 and released with a price tag of $34,000.) Like Zulresso, Zurvuvae (zuranolone) targets the unique hormonal components of the condition. Unfortunately, the drug’s manufacturer gave it a price tag of nearly $16,000—which, while lower than that of its IV-based predecessor, still points to the glaring need for improved, equitable access to game-changing treatments.

Also key to addressing postpartum health is normalizing the mental strain of this period—and the necessity of seeking support in the first place. That’s the message behind the September launch of the postpartum care campaign, “Who’s Mothering the Mother?” by maternal nutrition brand Chiyo, pelvic floor physical therapy provider Origin, formula brand Bobbie, and postpartum recovery brand Anya. The campaign’s downloadable postpartum care journal and postpartum meetups are meant to raise awareness for the importance of actively supporting new moms. So, too, are the new federal Task Force on Maternal Mental Health and awareness campaign for postpartum depression, both launched this year by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). What these developments readily acknowledge is that the postpartum phase brings unique challenges for mental health—and the people within it need and deserve a proportional level of support.

Such a recognition requires dismantling long-held expectations around postpartum in this country. “We’re often told that childbirth is supposed to be the greatest thing that’s ever happened, and it’s supposed to be nature, and I’m supposed to just instinctively know what to do,” says Emilie Fritz Veloso, founder and CEO of One Tribe, a pre- and postnatal wellness and educational center slated to open in January 2024 in Miami. It will bring together a variety of pregnancy- and postpartum-focused practitioners (like nutritionists, lactation specialists, and acupuncturists) and programming (such as pre- and postnatal yoga) under one roof to provide seamless care as well as community for the new and soon-to-be mother. “We’re not meant to parent in isolation or with just a partner, but with a tribe of other people,” says Veloso, of the center’s purpose and name. The company will also launch a virtual version of its classes in 2024 to reach people all over the U.S.

The same ethos underscores other newcomers in the postpartum space, like Motherocity, a postpartum tracking application launched in 2022 that uses daily check-ins to monitor and forecast a new mom’s physical and mental health. Upon downloading the app, a user will be prompted to fill out a postpartum care plan (e.g., “When I’m feeling lonely or disheartened, I’d like a hug or a hot meal”) and invite their supporters. As their mood fluctuates, those supporters will be notified of when and how they can help accordingly, “which streamlines the process of building your village,” says Motherocity founder Lydia Simmons, who is currently fundraising and plans to surpass 20,000 downloads in 2024.

The Fourth Trimester’s Delicate Transition

New York City–based relational fitness brand Peoplehood launched Motherhood this year with a similar community-oriented goal. Motherhood offers 60-minute guided group conversations for moms “to allow them the space and time to take a temperature check on how they’re doing,” says Peoplehood co-founder Julie Rice. Also this year, psychotherapist Chelsea Robinson, LCSW, launched Mama’s Modern Village to offer virtual and in-person group coaching on the identity-related transitions of matrescence, which she says “impacts a woman in every facet of her life: physically, emotionally, psychologically, hormonally, economically, and politically.”

Facilitating support for this “delicate transitional phase” of new motherhood is also the role of the postpartum doula, says doula Latham Thomas, founder of doula and maternity lifestyle brand Mama Glow. She notes a recent uptick in usage of postpartum doulas, particularly since the start of the pandemic, and a trend toward extending doula care for several months postpartum.

Chanel L. Porchia-Albert, founder and CEO of Ancient Song, a birth-justice organization that offers doula services to low-income people of color, expects that in the coming years, access to postpartum doulas will chart a similar growth trajectory as that of birth doulas. Ten states and the District of Columbia now cover doula care under Medicaid—which, in 39 states and D.C., has also recently been expanded from just 60 days to a full 12 months postpartum. This year, Mama Glow also announced a partnership with Blue Cross and Blue Shield offering access to doula services for members of the Blue Cross and Blue Shield Service Benefit Plan (which covers federal employees) who have a high-risk pregnancy and live in New York or Georgia. Such increased access to doula care doesn’t just have the power to improve birth outcomes7; it will also support postpartum mental health, too, with people who receive doula care during labor and birth showing a 65 percent reduced risk8 of developing PMADs.

“This kind of policy change is encouraging folks to have more conversations around postpartum care, as is the advocacy work of doulas and midwives, who have been saying for years, ‘Yes, we appreciate the fact that you are talking about doulas in the sense of birth, birth, birth, but what happens after the baby gets here?’” says Porchia-Albert. In 2024, Ancient Song will partner with Healthline Media to launch a postpartum care campaign with classes designed to educate partners and other loved ones of new moms on how they can best step up to support them.

For all of this emerging programming to make the biggest impact, however, the U.S. also needs a national paid family leave program—so that the postpartum transition isn’t rushed for financial reasons. “As a sociologist, I would like to think that as a society, we should be invested in supporting and caring for the people who are creating our future,” says Christine H. Morton, PhD, research sociologist at California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative (CMQCC). There’s certainly interest in paid leave at the federal level (including a new House Bipartisan Paid Family Leave Working Group) and on the ground (see: celebrity-backed public campaigns), but whether we’ll see any progress still hinges on bipartisan action across Congress.

In the meantime, education around the socioemotional reality of matrescence can reinforce the necessity of postpartum support, says clinical psychologist Aurélie Athan, PhD, whose research is credited with reviving the term matrescence and expanding it to encompass the modern-day reality of motherhood: “We need more spaces in the community to both educate and assist mothers to reflect on these identity shifts and advocate for real help before their distress reaches clinical levels.” This kind of care can act as a parachute for new parents, so that after taking the cliff-dive into postpartum, they have a chance at a soft landing.

PUBLISHED FEBRUARY, 2024, WELL+GOOD

- Shuman, Clayton J et al. “Postpartum depression and associated risk factors during the COVID-19 pandemic.” BMC research notes vol. 15,1 102. 14 Mar. 2022, doi:10.1186/s13104-022-05991-8

- Song, Ju-Eun et al. “Effects of a maternal role adjustment program for first time mothers who use postpartum care centers (Sanhujoriwon) in South Korea: a quasi-experimental study.” BMC pregnancy and childbirth vol. 20,1 227. 16 Apr. 2020, doi:10.1186/s12884-020-02923-x

- Cho, Hahyeon et al. “Association between social support and postpartum depression.” Scientific reports vol. 12,1 3128. 24 Feb. 2022, doi:10.1038/s41598-022-07248-7

- Henderson, Vida et al. “Understanding Factors Associated with Postpartum Visit Attendance and Contraception Choices: Listening to Low-Income Postpartum Women and Health Care Providers.” Maternal and child health journal vol. 20,Suppl 1 (2016): 132-143. doi:10.1007/s10995-016-2044-7

- Brown, Clare C et al. “Mental Health Conditions Increase Severe Maternal Morbidity By 50 Percent And Cost $102 Million Yearly In The United States.” Health affairs (Project Hope) vol. 40,10 (2021): 1575-1584. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2021.00759

- Trifu, S et al. “The neuroendocrinological aspects of pregnancy and postpartum depression.” Acta endocrinologica (Bucharest, Romania : 2005) vol. 15,3 (2019): 410-415. doi:10.4183/aeb.2019.410

- Sobczak, Alexandria et al. “The Effect of Doulas on Maternal and Birth Outcomes: A Scoping Review.” Cureus vol. 15,5 e39451. 24 May. 2023, doi:10.7759/cureus.39451

- Falconi, April M et al. “Doula care across the maternity care continuum and impact on maternal health: Evaluation of doula programs across three states using propensity score matching.” EClinicalMedicine vol. 50 101531. 1 Jul. 2022, doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101531